Hēki operations update:

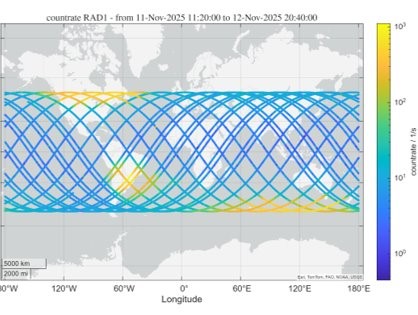

As previewed in this post, Hēki has started regular operations, collecting data from the radiation sensors while increasing the magnetic field from 0 to 500mT in 100mT steps over this past week. Yesterday we reduced the field to 450mT, and we will decrease it in 100mT steps to 0mT again by early next week. The radiation sensor data acquired as a function of magnetic field address one of Hēki’s mission success criteria. The data is currently being analysed in collaboration with our colleagues at the Czech Technical University in Prague, and the results will be used to refine our plan for operating Hēki for the remainder of the mission.

Thermal characterisation

Thermal control was one of the largest challenges our team faced when designing Hēki – in other words, making sure that all of Hēki’s components will remain within a safe temperature range over a range of conditions (as discussed in this post).

Image: Nanoracks External Plaform (NREP) – enclosing Hēki – surrounded by other experiments on the Japanese Experiment Module External Facility (JEM-EF). The structures around it may shade Hēki or allow sunlight to heat it, depending on how they are oriented relative to the Sun.

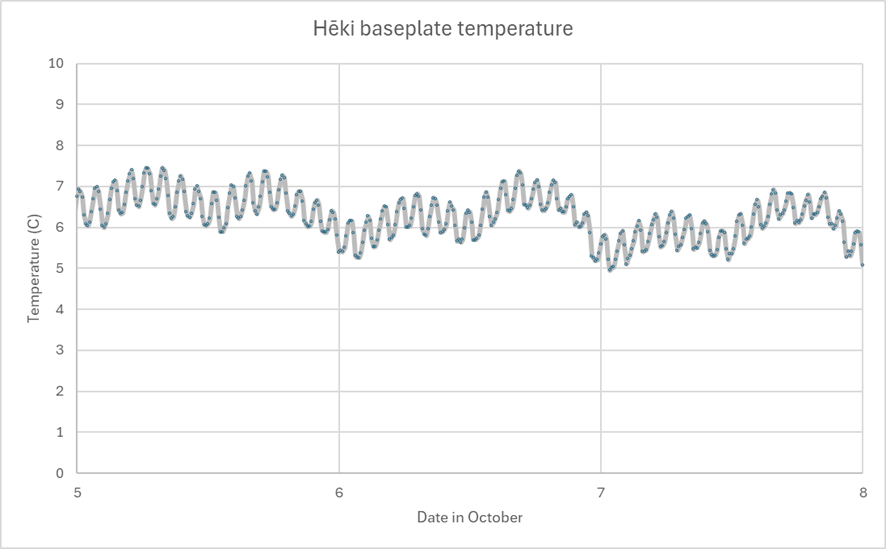

After initial power-on, Hēki’s temperatures were relatively stable on average, though there were temperature cycles approximately every 90 minutes as the International Space Station (ISS) orbits the Earth, passing in and out of sun and shadow. This orbital cycle results in continual changes to the lighting on Hēki (and the structures surrounding it), but the resulting temperature variations have been small.

Image: Hēki baseplate temperatures over several days in early October, illustrating the ~90 minute day/night cycle as the ISS orbits the Earth. In addition to the orbital cycle, changes in light reflecting off of ISS structure and the land, sea, and clouds below also generate small variations in temperature over time.

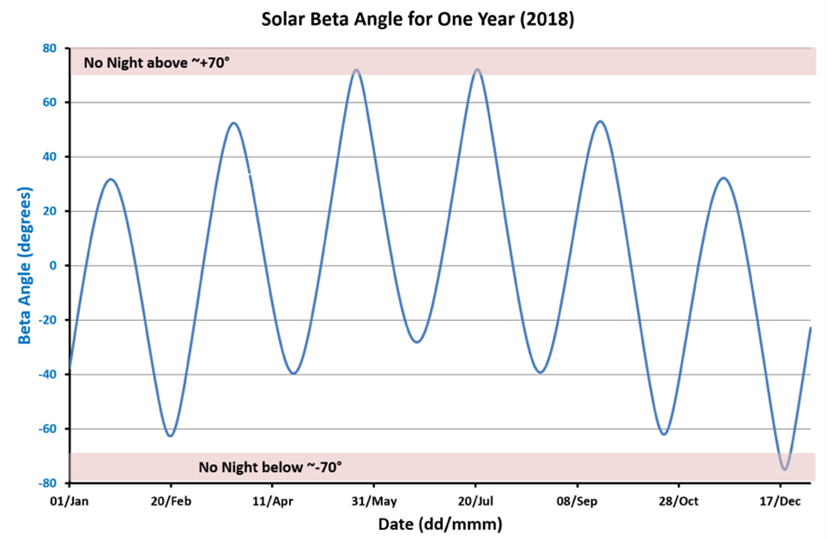

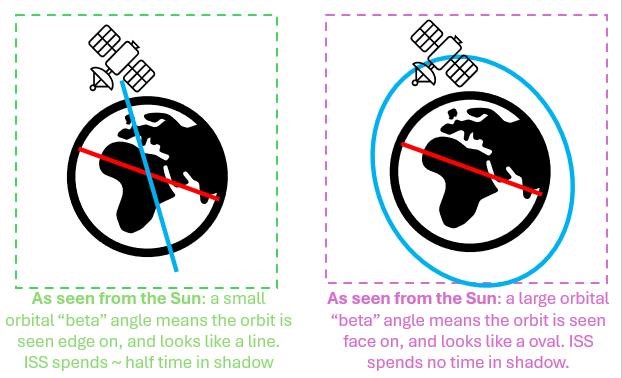

In addition to the ISS orbital motion, there are two further factors affecting Hēki’s temperatures. The first is the ISS “attitude” – how the ISS structure is oriented relative to the Sun and Earth as it orbits. The attitude determines which ISS components face the Earth vs. space, which are pointed forward or backward as the ISS travels in its orbit, and so on. The second factor is the ISS “beta angle”, which is defined as the angle between the space station’s orbital plane – a plane defined by the circle of its orbit about the Earth – and the direction of the Sun. The beta angle slowly changes, making several cycles over a year.

Together, the ISS attitude and the beta angle determine which parts of the space station will receive Sun and which will be in shadow as it orbits the Earth.

Image: The ISS circles the Earth at an orbital inclination (angle of the orbit plane to the Equator) of 51.6°. The angle between this orbital plane and a line to the Sun is called the “beta” (β) angle. (source: AMS – Thermal Operation).

Image: ISS beta angle calculated for the year 2018 (source: AMS – Thermal Operation)

Image: The ISS beta angle changes as the Earth circles the Sun, and the ISS orbit precesses around the Earth. The beta angle is one of the factors determining how much sun is received by parts of the ISS – and thus whether experiments on the ISS will get warmer or cooler over time.

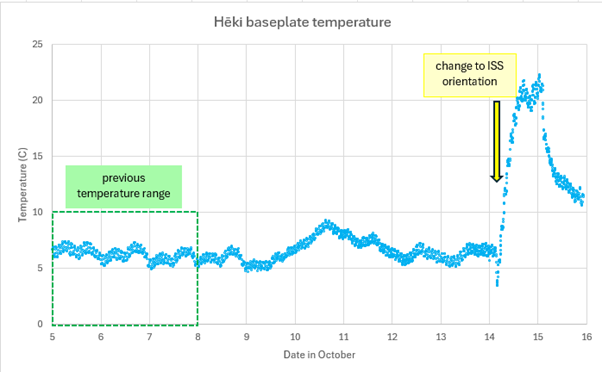

Recently, the ISS changed its attitude for a maintenance activity, resulting in a very sudden change to Hēki’s “thermal environment” – the sunlight and shadow on Hēki and the structures around us. The mission management team at Voyager Technologies had informed us about the upcoming manoeuvre, and Hēki’s temperature sensors immediately recorded the change as it happened!

Image: change in Hēki’s baseplate temperatures resulting from an ISS attitude change

Hēki’s temperatures decreased once the ISS returned to its previous attitude, but they have started increasing slowly again with the change in beta angle. Our modeling predicts that the temperatures will continue to increase over the next week before starting to decrease again. During this transition, our team will monitor Hēki’s temperatures and respond as needed to ensure everything remains with safe operating limits.

Characterising Hēki’s response to its changing thermal environment is a crucial component of validating its technology for future spaceflight applications.

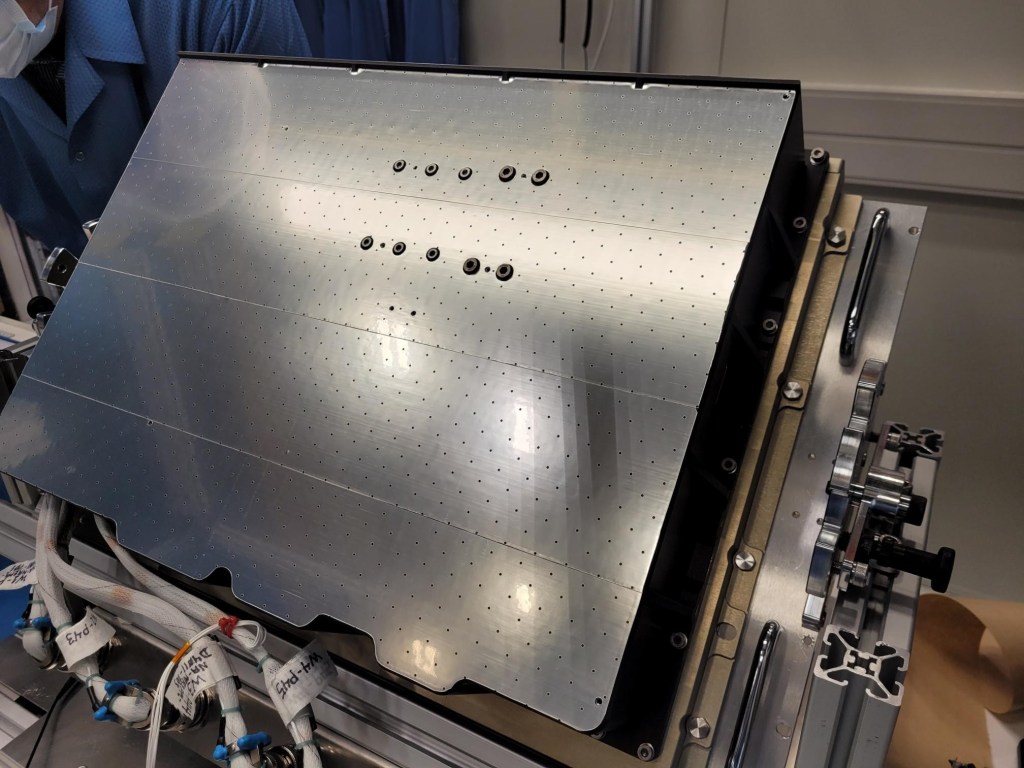

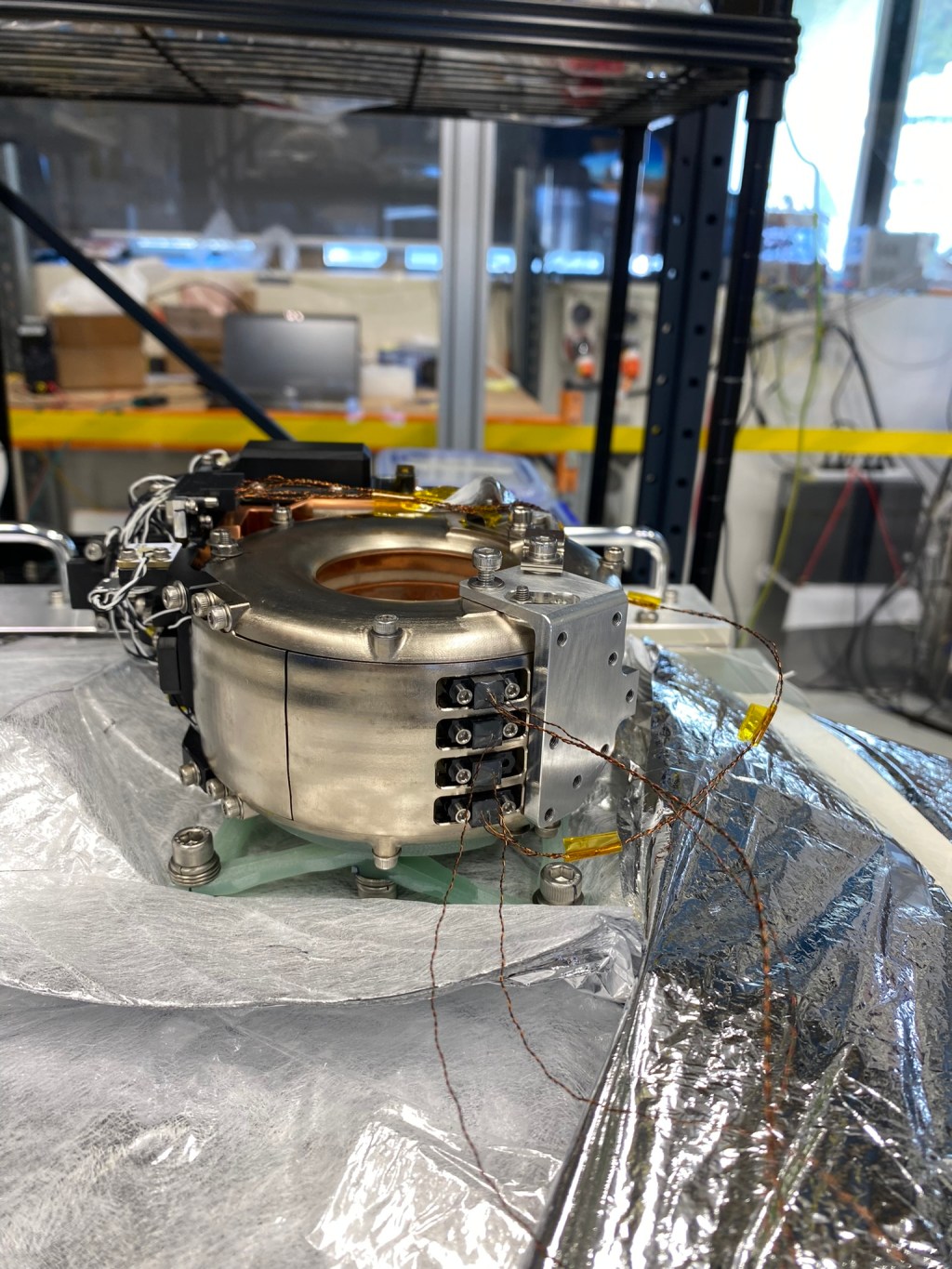

Header image: Hēki’s “silver teflon” coated radiator surface, which reflects sunlight and efficiently radiates away heat to maintain safe operating temperatures.

Leave a comment