The Hēki team has just completed the third of three required magnetic field cycles from zero to 500mT, the highest field strength planned for our mission on the ISS. Checking off the rest of the mission duration goal – success criterion #10, below – will require successful Hēki operations for the nominal 15-week mission duration (achieved in mid-January). We are currently in discussions to extend our mission beyond 15 weeks, so look for more news on that soon!

We’ll continue to cycle Hēki’s magnetic field throughout the remainder of our mission and use the available time to characterise the system as fully as possible. In the meantime, it is rewarding for our team to be making significant progress against the remaining mission success criteria.

Hēki Success Criteria

| Before Launch | ||

| ✅ | 1 | Build low-power, superconducting magnet system |

| ✅ | 2 | Verify Hēki can survive journey to – and operations in – space |

| ✅ | 3 | Comply with NASA safety requirements |

| ✅ | 4 | Demonstrate successful communication between Hēki and space station computer simulator |

| ✅ | 5 | Verify Hēki team’s readiness for operations in space |

| In space | ||

| ✅ | 6 | Successfully power on after installation on space station |

| ✅ | 7 | Verify magnet is cooled to superconducting temperature (-200C) |

| ✅ | 8 | Meet or exceed required magnetic field (300mT) |

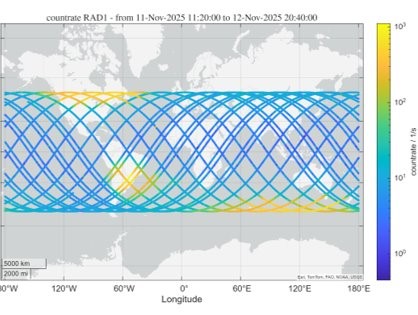

| 9 | Measure effectiveness of magnetic field as a shield for space radiation |

| 10 | Demonstrate successful operation throughout the mission, including at least three magnetic field cycles |

| After return to Earth | ||

| 11 | Characterize Hēki to determine if there has been any degradation in performance | |

| 12 | Repeat characterization after forcing a magnetic “quench” to show that Hēki can safely dissipate stored energy if superconductivity is lost. | |

Completion of Hēki’s remaining in-flight success criterion – #9 above – is in progress as well, with radiation sensor data being collected as a function of magnetic field. We’ll continue to collect this data as conditions allow… and we’re now learning enough about how Hēki responds to its environment to identify what those safe operational conditions are!

As noted in this post, maintaining Hēki’s components within operational temperatures was identified as a significant challenge early in our planning. Component temperatures change over time as Hēki – and the structures around it – see changing amounts of sun and shadow. Over the past week, Hēki’s temperatures got warm enough to that we needed to power down our radiation sensors to protect them from exceeding safe operating temperatures. Our thermal model predicts that the radiation sensors’ temperatures will return to a safe range in the next several days and remain there for the next several weeks. We’ll continue to monitor Hēki’s temperatures and power the radiation sensors back on soon to resume data collection. Further, our team is gathering valuable insight on how to improve our designs for future missions, including ensuring that components will be less susceptible to extremes of temperature.

In the meantime, researchers are already analysing the data received so far, and their findings on both the magnet/flux pump performance and radiation sensor response will shape our operations plans for the remainder of Hēki’s mission.

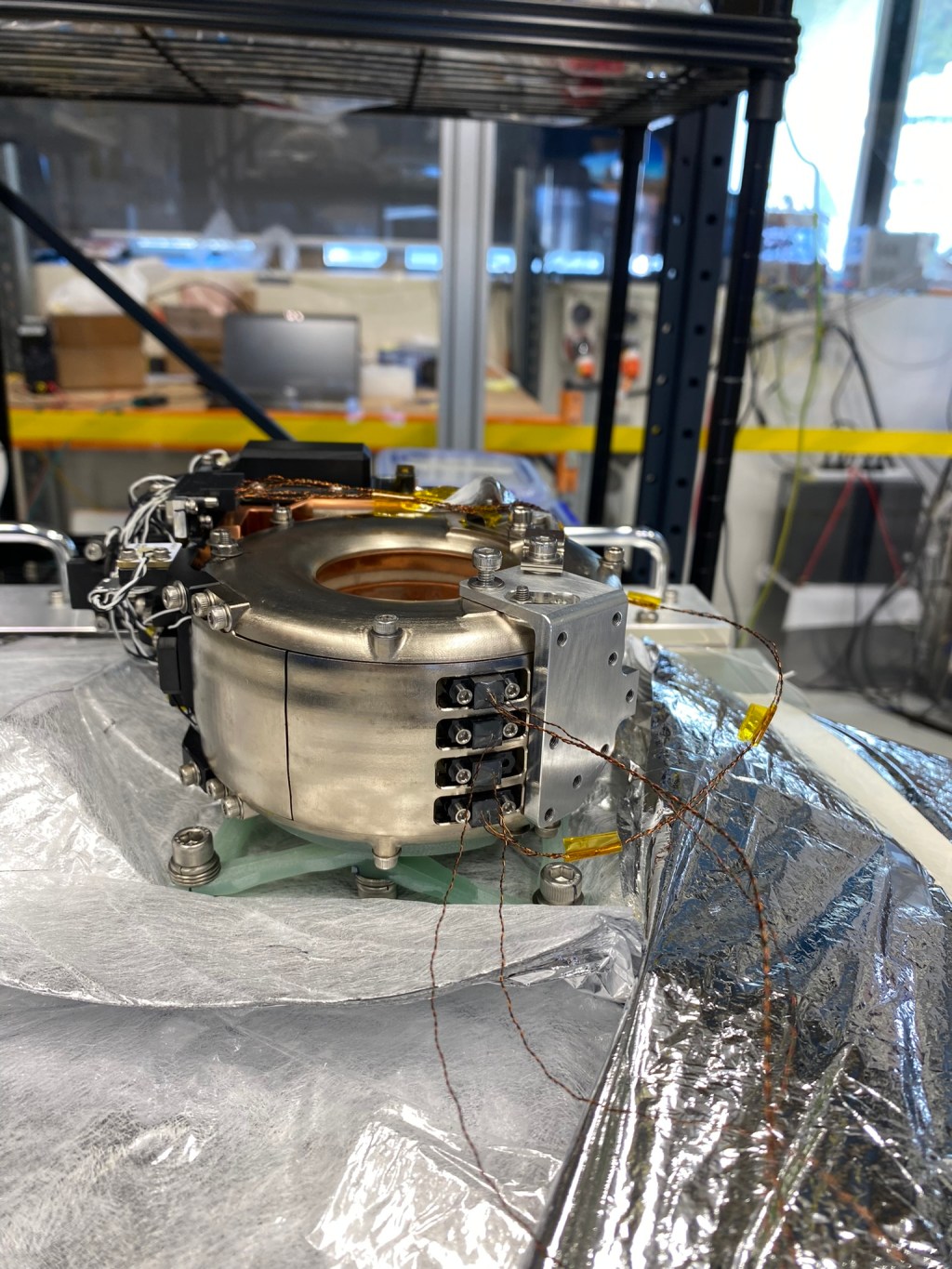

Header image: Hēki’s donut-shaped magnet during assembly for flight. The magnet is enclosed in steel shield which serves to minimize any “stray” magnetic field that might potentially interfere with surrounding electronics. Hēki’s flux pump – which energizes the magnet once both are cooled to about -200C – is located behind the magnet. The magnet/flux pump assembly is supported by a fibreglass structure which helps to thermally insulate the magnet from the warmer baseplate during operation.

Leave a comment