Operations Update:

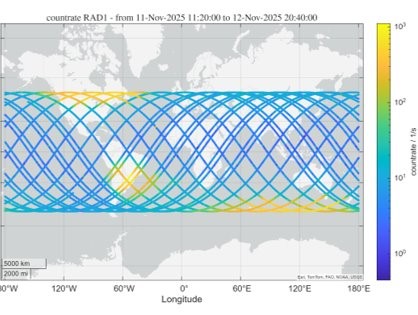

Hēki is making good progress toward completing the two remaining on-orbit mission success criteria. We’ve finished the second of three required magnetic field cycles and the first cycle where radiation sensor measurements have been acquired as a function of magnetic field. Hēki remained at zero field over the weekend – collecting a “baseline” radiation measurement – and has started another cycle this week, this time using a software feature which automatically optimises the flux pump magnet charging waveform as the temperature changes. This “temperature compensation” feature will be characterised over the next two weeks and is designed to make Hēki’s flux pump operations more efficient.

Hēki mechanical design, analysis and test

Max Goddard-Winchester, Mechanical Engineering Lead

Designing and assembling Hēki required a multidisciplinary team divided into individual subsystems. With my background in mechanical engineering, I was responsible for the structural subsystem, which drew on my experience with design and simulation.

The mechanical design process to qualify experiments for space flight requires consideration of many factors that could be neglected for a similar experiment running in our lab. In the case of Hēki, there were several such aspects that required in-depth analysis to ensure that the payload was prepared for its journey to the ISS, and for the time it would spend in the harsh environment of space.

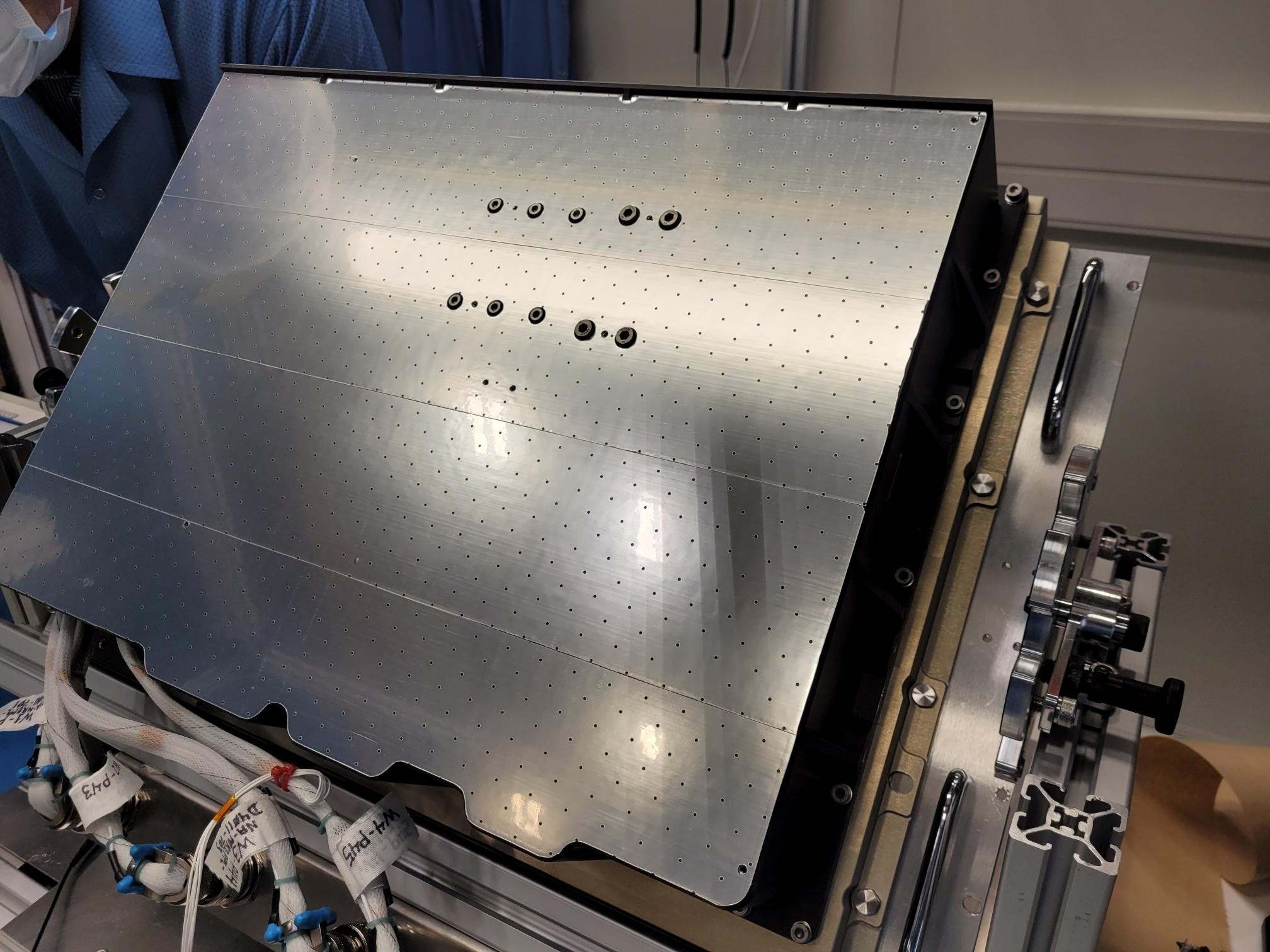

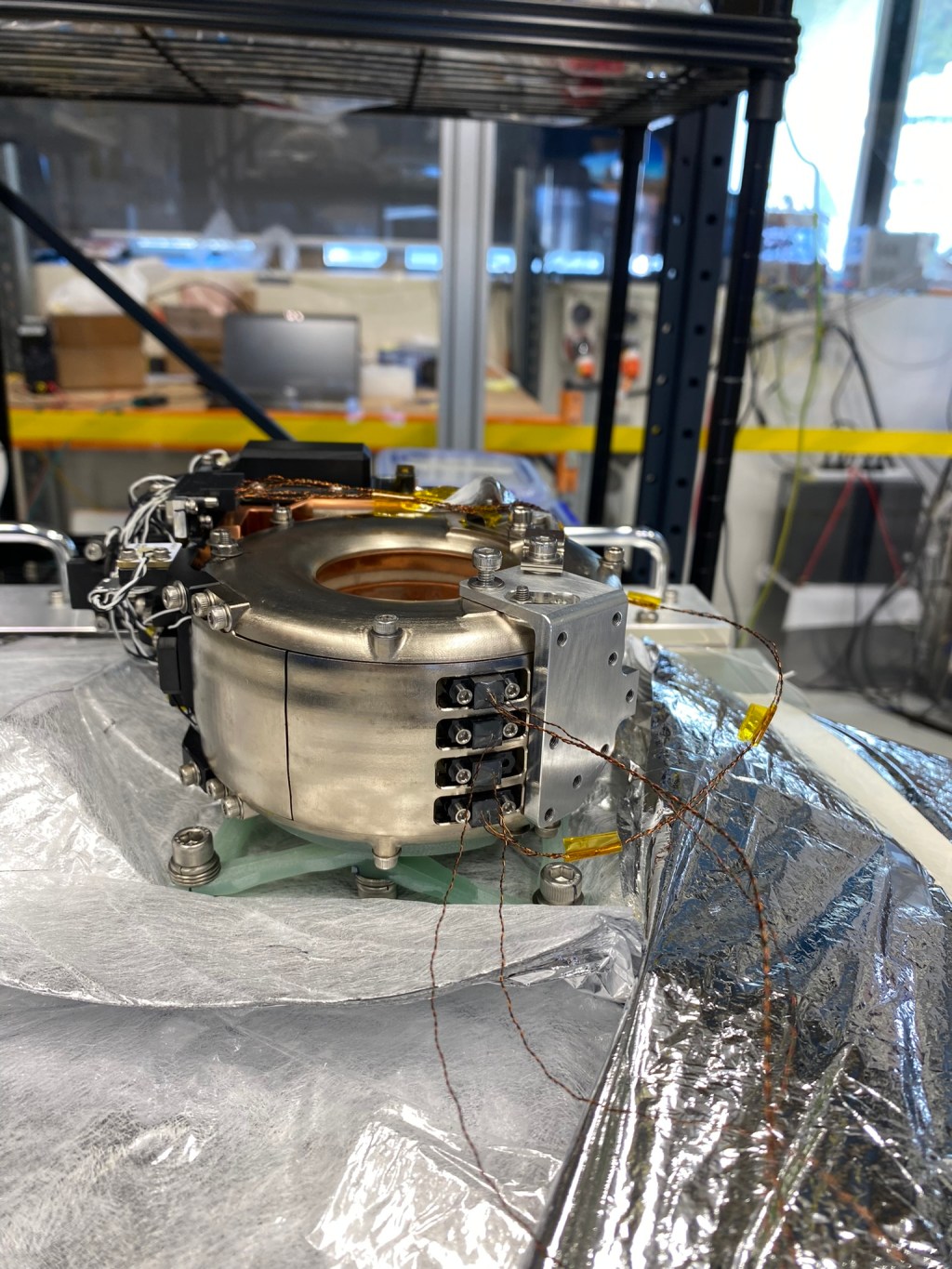

On Earth, we have many tools for maintaining control over the temperature of our equipment: an atmosphere which can transfer heat, space for bulky water-cooling systems, and as much power as required to operate refrigeration and heating systems. In the near vacuum environment outside the International Space Station, however, we use a soda-can-sized cryocooler to keep Hēki cold. This cryocooler must run on the limited power available and has few options for getting rid of the heat that it generates. To address this latter problem, the surface of Hēki exposed to space has been treated with a delicate coating of silver coated Teflon to act as a radiator. This radiator emits the heat created by the cryocooler and its electronics away from Hēki in the same way that the radiant heat from the sun reaches us.

Image: Hēki’s radiator surface, covered with a “silver Teflon” material which is both reflective and highly emissive (effective to radiating heat away)

Aboard a space station that is in constant free-fall, the safety of its residents and the systems that keep it operational are paramount. Therefore, Hēki had to undergo a variety of analyses to prove that it would not fail in a manner which posed a risk to the ISS or its crew. These analyses included computer simulations of the vibrational loads of the rocket launch and the force of an accidental astronaut kick to Hēki’s enclosure. The results of these simulations were thoroughly reviewed and were only accepted once they showed that Hēki’s design provided a significant margin of safety in the required test cases.

Image: Structural stress analysis of “kick load” applied to Hēki’s passive-side housing structure. Left: computer-generated drawing of the structure showing location and size of the applied force (in pink). Right: analysis showing resulting stresses on the structure; the maximum stress location and magnitude are shown. This maximum stress was then compared to the material properties of the housing material (aluminium) to ensure that Hēki’s design would survive the applied load with significant margin.

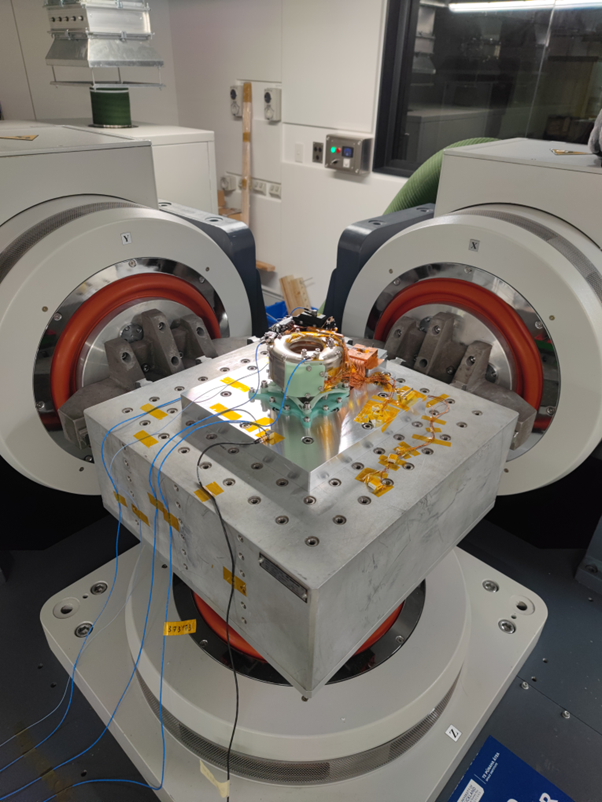

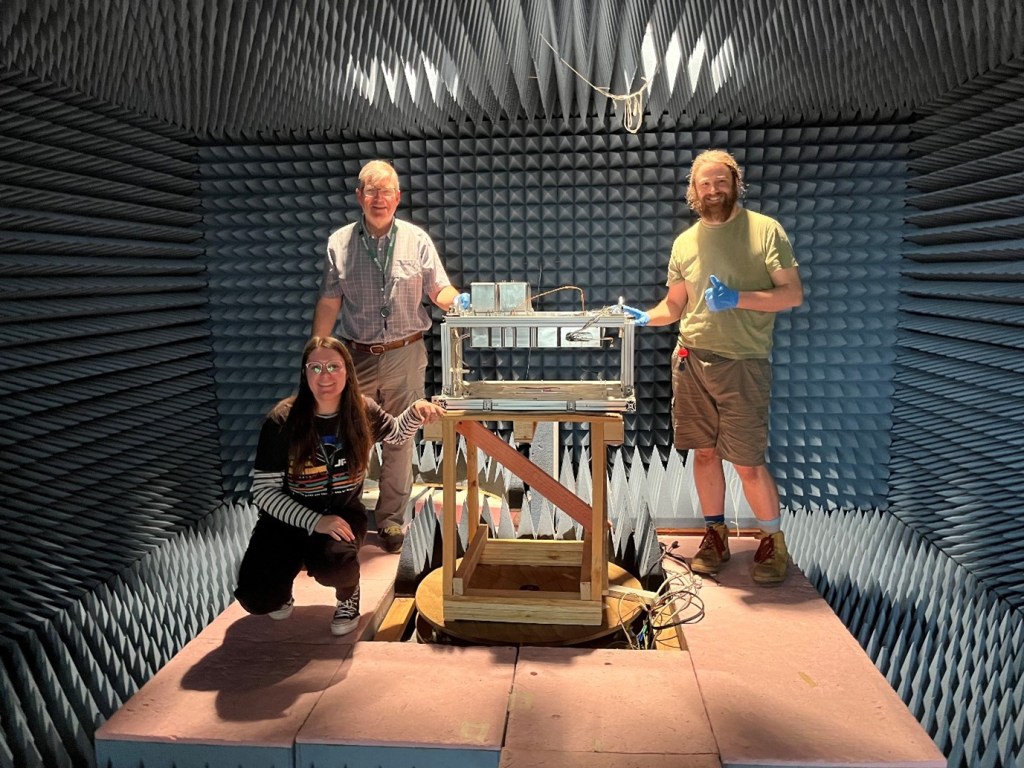

As reassurance that Hēki itself would survive a rocket launch, the magnet and flux pump at the heart of the system were tested on a 3-axis shake table at the University of Auckland. During this test, these components survived vibrations greater than anticipated in our launch. Functional checkouts were successfully completed after these shake tests, which confirmed that they had caused no deterioration in performance.

Image: Hēki’s magnet and flux pump on the “shake table” at University of Auckland. This facility simulated the vibrations Hēki experienced during launch. Early testing was crucial to verify that Hēki’s design – which needed to be compact, strong, and light – would survive its journey to the International Space Station.

With the strict margins of safety required from design and simulation, the careful consideration of thermal loads a payload can expect in space, and the physical testing that it underwent, Hēki was well equipped for its journey to the ISS. Its successful installation and smooth operation are a testament to these efforts, and each mission criteria ticked off is a tremendous payoff.

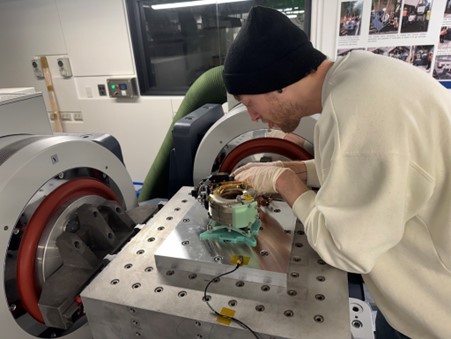

Header image: mechanical engineer Max Goddard-Winchester prepares Hēki magnet and flux pump assembly for vibration testing at the National Satellite Test Facility at Te Pūnaha Ātea, University of Auckland.

Leave a comment