Day 2 Operations Completed Successfully!

Hēki’s temperatures remained within safe limits overnight. Our team observed the normal temperature changes expected when Hēki passed through sun and shadow as the ISS orbits the Earth. The highest priority today was to check out Hēki’s remaining subsystems: the cryocooler that cools the magnet to cryogenic temperatures (-200C) and the flux pump that will energise it to field.

We started by verifying that the flux pump generated the expected voltage signals on Hēki’s magnet coils. The magnet was not yet cryogenic so no significant field was generated by this activity, but our team was able to confirm the flux pump and its control electronics were all working as expected.

Our next step was to turn on Hēki’s cryocooler at minimum power so that we could verify the cooler had survived its journey to the ISS. This test was also a chance to verify that the heat that the cryocooler pulls out of the magnet can be safely radiated away without warming Hēki’s electronics out of their safe operating range. We will continue to monitor Hēki’s temperatures through tomorrow, but the results of the cryocooler test are looking very promising at this time.

In parallel, the Hēki and Voyager Technologies teams worked together to enable the streaming of high-rate telemetry from Hēki to the ground to make it easier for our team to monitor future test activities.

The next few days will include more thermal characterisation. We’ll ramp up the maximum cooler power as needed to bring the magnet to cryogenic temperatures while monitoring to ensure that all of Hēki’s electronics remain within safe temperature limits. Once the magnet is cryogenic, we’ll start to energise it and test its performance in space… a milestone our team has been working toward for the past 5 years!

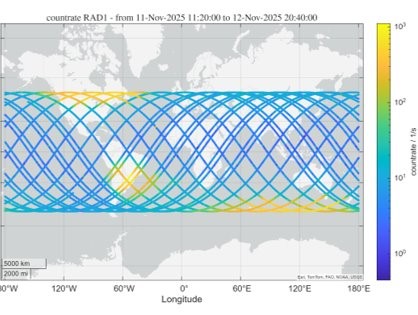

Hēki’s HardPix radiation detector experiment

Radiation in space comes from a variety of sources, including astronomical objects – for example, black holes and supernovae – as well as our own Sun. A significant fraction of space radiation consists of electrically charged particles such as electrons and ionized atomic nuclei. These particles’ charge means that they will be deflected by magnetic fields. The Earth’s magnetic field – in addition to our atmosphere – helps shield those of us on the ground, but radiation exposure remains one of the challenges of spaceflight for both people and electronics. Future long-duration crewed flights will need a system to protect astronauts from this flux so that they remain healthy throughout their journey.

Hēki includes two “HardPix” radiation detectors provided by the Czech Technical University in Prague. HardPix is based on the pixel sensor Timepix3 which captures tracks of particles in high resolution, allowing us to identify the type of particle and measure its energy deposited in each pixel. The two sensors are placed significantly different distances from the magnet – one close to the magnet and one further away -allowing the team to study both the radiation’s natural variability and the deflection effect of the magnetic field. Data will be collected throughout Hēki’s mission and analysed to guide the design of radiation mitigation systems for future spacecraft. Characterising the impact of the magnetic field on the charged particle environment is one of Hēki’s success criteria.

HardPix detectors were selected for Hēki due to their scientific capabilities, miniature size and space heritage. Two detectors were already launched to space in 2023 and 2025, and there are plans to place HardPix onboard the planned Gateway station orbiting the Moon and even to use them for the mapping of water deposits directly on lunar surface onboard a robotic rover.

Thank you to Robert Filgas (Czech Technical University in Prague) for his review & contributions to this article.

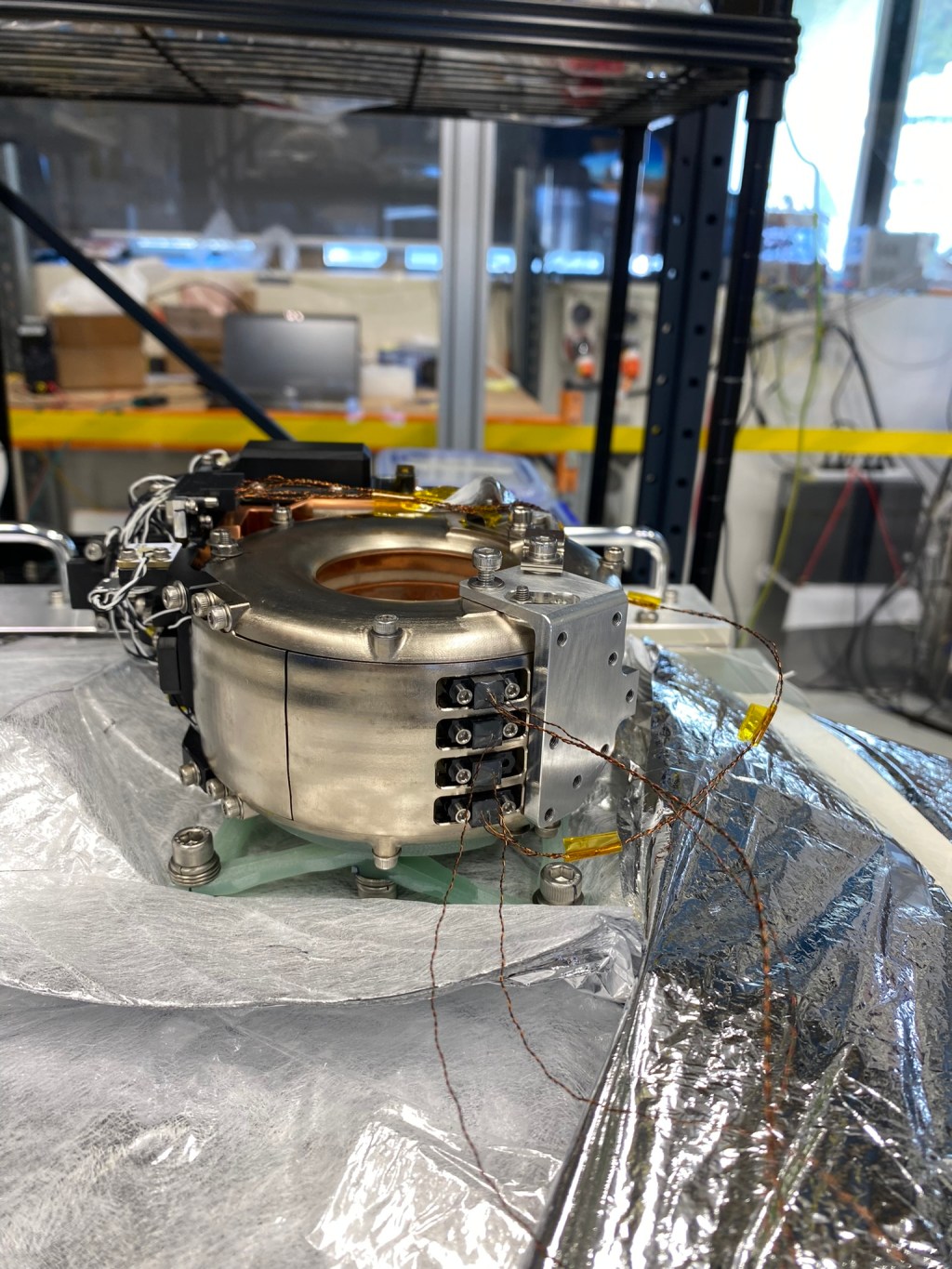

Image: Annotated diagram of Hēki, showing major subsystems, including the radiation detectors. Active side (left) faces Earth when installed on ISS and is designed to radiate away waste heat via a silver teflon surface, which is both highly reflective and emissive. Passive side (right) contains the cryogenic components. Both active and passive housings are mounted to a supporting baseplate, which was integrated with the Nanoracks External Platform (NREP) by the ISS crew.

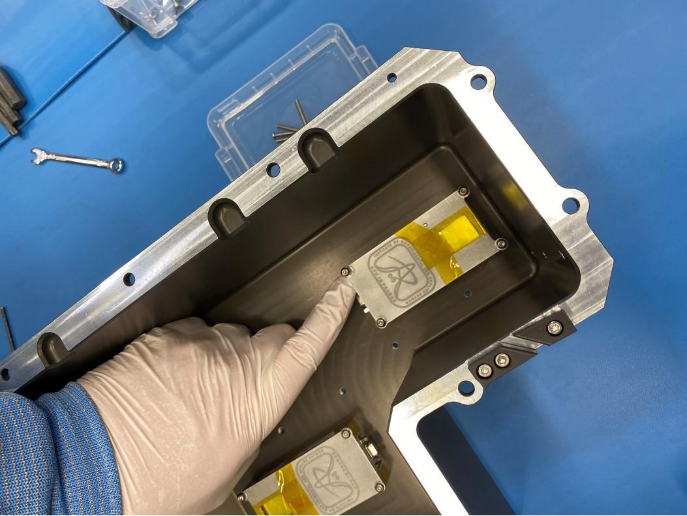

Image: engineer installing HardPix radiation detectors inside Hēki’s aluminium cover. Credit: Zoë Jaeger-Letts

Leave a comment